by

Pam Killeen

September 26, 2025

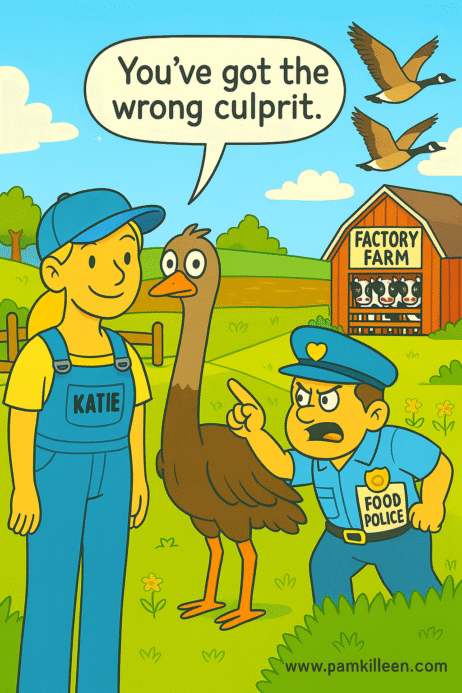

The wrong target

Katie Pasitney, spokeswoman for Universal Ostrich Farms in Edgewood, B.C., says the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) told her that migratory birds likely contaminated her farm’s drinking pond—now the basis for ordering her entire flock of ostriches to be destroyed.

On December 31, 2024, lab tests on two ostrich carcasses came back positive for H5, later confirmed H5N1. The CFIA then invoked its stamping‑out policy and ordered the flock depopulated. In all, 69 birds died during the December–January outbreak; since mid‑January 2025, there have been no reported deaths and the surviving flock has been described in court materials as healthy for months. Under CFIA’s approach, once a premises is declared infected or exposed, all birds on that premises are slated for depopulation—the policy does not provide for re‑testing survivors to spare individuals.

The question is obvious: if virus‑carrying wild birds contaminated the pond, why is the hammer falling on the ostriches? They’re victims, not vectors (carriers or spreaders of disease)—and aiming at them lets upstream environmental sources off the hook.

What recent fieldwork shows

New field research from California’s dairy hot spots should be a wake‑up call. On 14 H5N1‑affected dairies, scientists found infectious H5N1 in milking‑parlor air during milking and viral RNA throughout the wastewater stream, with infectious virus in some wastewater samples—including manure lagoons that migratory birds visit. In plain terms: industrial processes can aerosolize and concentrate virus, and lagoons can feed it back to wildlife, creating a plausible bridge from factory‑farm operations to smallholdings like Universal Ostrich Farms.

It’s a system problem, not a one‑off

Industrial livestock systems generate enormous volumes of untreated waste, stored in open lagoons or spread on fields. Factory Farm Nation 2024 estimates 1.7 billion confined animals in the U.S. producing ~941 billion pounds of manure each year, much of it untreated. Storms and floods routinely overwhelm lagoons, flushing pollution—and potentially pathogens—into waterways. If regulators are serious about stopping environmental transmission, this is where they should focus first.

B.C.: reacting, not solving

B.C.’s own records show repeated avian‑flu clusters in the Fraser Valley. The usual response—“cull everything nearby”—makes headlines, not progress. If infectious virus is in milking‑parlor air and farm wastewater that migratory birds frequent, a real response starts at the top: identify and fix the source of contamination, then take concrete steps to disrupt environmental spread (for example, treat wastewater before field use, cover or seal manure lagoons, deter wild birds from contaminated sites, and filter air in barns and parlors).

To be precise about policy: CFIA’s public AI (Avian Influenza) guidance centers on depopulation, movement controls, biosecurity, and cleaning & disinfection; it does not require upstream environmental controls like lagoon covers, wastewater treatment, or air monitoring in milking parlors. That policy gap leaves the main environmental reservoirs largely unaddressed while small farms face culls. Killing apparently healthy ostriches without first testing and fixing upstream sources isn’t just shortsighted. It’s scientifically reckless.

Culling survivors defies common sense

Even more misguided is the notion of culling animals that survive an illness; such a policy defies both logic and basic science. When a person recovers from a bad cold or flu, we recognize their recovery as a sign of resilience and restored health—not as a biohazard requiring elimination. The same principle should apply to other creatures: an ostrich (or any animal) that overcomes infection is demonstrating natural resilience, likely even carrying antibodies that make it less of a threat going forward. In fact, a University of British Columbia expert provided an affidavit attesting that these surviving ostriches have developed immunity to avian flu—underscoring how senseless a cull would be. You, the reader, have probably had a bad cold or flu—should that mean you should be culled too? The absurdity of the question itself exposes how irrational blanket culls of healthy survivors truly are.

Scale magnifies risk—small farms pay the price

The biggest danger of factory farming isn’t just pollution—it’s the overwhelming scale of these operations. When avian flu hits huge egg or poultry complexes, mass depopulations ripple through supply chains—but big firms usually survive the shock. Small family farms don’t have that buffer. The long‑term trend is stark: about 733,000 farms in 1941 has fallen to 189,874 farms in 2021. Heavy‑handed stamping‑out policies accelerate that decline, pushing out small, independent operations—often the very farms trying to do things right. These farms feed their neighbors, support local economies, and care for the land. We need more of them, not fewer.

A source‑first plan

Test the environment and publish the data. Sample the ostrich pond (inflows/outflows), nearby sump pits, fields irrigated with reclaimed wastewater, and manure lagoons for H5N1 RNA and infectious virus. Publish Ct values, culture results, and chain‑of‑custody. This mirrors the California protocol and would confirm—or rule out—an environmental route tied to industrial waste streams.

Monitor the air where exposure occurs. Use validated air samplers in nearby milking parlors and downwind locations. If infectious virus is present during milking, target mitigation where transmission actually happens: respiratory and eye protection, rigorous disinfection of milking equipment, safe handling/treatment of contaminated milk, and treatment of wastewater before field use.

Limit wildlife access to contaminated sites. If lagoons draw migratory birds, require deterrents or covers, upgrade waste handling, and set measurable treatment standards. Leaving that system untouched while slaughtering birds on a small farm is regulatory theater, not public health.

Do the right things—in the right order

This isn’t a plea to do nothing. It’s a plea to do the right things in the right order. If the CFIA can show recent, farm-specific evidence that the ostriches are infected—based on proper sampling and clear documentation—it will have a stronger case. But if the evidence points to industrial air and wastewater as the drivers of environmental contamination, then mass‑culling a pond‑drinking flock is both cruel and counterproductive.

Keep your eye on the source

Until we confront the open manure lagoons and airborne contamination coming from industrial livestock systems, culling ostriches will do nothing to protect public health. It won’t stop the virus. It won’t make British Columbians—or our farms—any safer.

What it will do is destroy one more small, independent operation while the real sources of infection remain untouched.

We don’t need more scapegoats. We need smarter policy.

It’s time for the CFIA to stop the cull, rethink its strategy, and start targeting the real sources of infection—like open manure lagoons, contaminated air, and industrial waste streams.

Pam Killeen is a health coach, podcaster, and co-author of the New York Times bestselling book The Great Bird Flu Hoax (2006). She writes and speaks extensively on health, nutrition, and systemic corruption in science and public policy.

References

1) We Animals. (2023, August 23). New report explores the role of factory farming in the spread of avian influenza. We Animals Media.

2) Campbell, A. J., et al. (2025). Surveillance on California dairy farms reveals multiple sources of H5N1 transmission [preprint]. bioRxiv.

3) Schnirring, L. (2025, August 4). Air, wastewater may play roles in H5N1 transmission on dairy farms. CIDRAP News.

4) Feed Strategy Staff. (2025, August 15). Study eyes air, wastewater as source of H5N1 transmission on dairy farms. Feed Strategy.

5) Food & Water Watch. (2024, September 21). Factory Farm Nation: 2024 Edition. Food & Water Watch.

6) Government of British Columbia – Ministry of Agriculture & Food. (2023, December 14). Avian influenza now detected at more than 50 farms (Information Bulletin). BC Gov News.

7) Statistics Canada. (2022, May 11). Land use, Census of Agriculture historical data (Table 32‑10‑0153‑01; formerly CANSIM 004‑0002). Statistics Canada.

8) Mehler Paperny, A. (2025, September 24). Canada pauses cull of ostrich flock that had cases of avian flu amid U.S. push to save them. Reuters.

9) Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). (2025, May 31). Basis for applying disease control measures at an avian influenza infected ostrich farm. CFIA.

10) Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). (2023, August 2). Cleaning and disinfection: avian influenza. CFIA.

11) The Canadian Press. (2025, Sept 22). A timeline of the fight to save a flock of ostriches in a B.C. farm. Halifax CityNews. (Dec 31, 2024: two carcasses H5→H5N1; Jan 15: last death; total 69.)

12) Global News / MacGillivray, K. (2025, Sept 6). Hundreds of B.C. ostriches given temporary reprieve from cull. (Court filing: “healthy for >230 days; last death mid‑January”).